Bio: Sh. Abul Hassan ´Ali ibn Hirzihum

Shaykh Abul Hassan Ali ibn Harzihim

d. 544 H. (1129 CE) in Fasqaddasa Allah sirrahu

Teacher Al-Qutb Abu Madyan al-Ghawth

.

Dar-Sirr article

Once Andalusian Malikism became states policy in Marrakech and Fez, as well as in Cordoba and Seville, Arab jurists acting under the authority of Almoravid governors set out to suppress dissenting opinions. As a part of this crackdown, all copies of al-Ghazali’s (d. 526/1111) I’hya’ ‘ulum ad-din were ordered confiscated and publicly burned. According to most historians, the banning of this work was due to al-Ghazali’s Shafi’i-inspired critiques of non-usuli legal traditions. Another reason, perhaps, was al-Ghazali’s belief, following his teacher Sidi Abul Ma’ali Abdelmalik Jawayni (d. 499/1105), that all knowledgeable Muslims—and not just the official ulama—could act as representatives of the Muslim community. According to this theory, all learned men had a right to be considered as “those who loosen and bind” (ahl al-hall wal ‘aqd) and could have a voice in the conformation or rejection of claimants to the throne. Since this wider group of ulama included both usuli dissidents and juridically-oriented Sufis, such views would not have been popular at the Almoravid court.

An immediate result of the suppression of al-Ghazali’s works was the spread of the usuli dissidence throughout Morocco. The most significant exponent of this movement was the Masmuda Shaykh Sidi al-Mahdi ibn Toumart (d. 524/1130) himself who were to become the founder of Almohad (al-muwahhidun—”unitarian”) movement. The Imam and Shaykh Ibn Toumart was joined to his opposition to the Almoravids by a number of Andalusian and Moroccan Sufis, whose journeys to the Muslim East had brought them into contact with Shafi’i jurists, Ash’ari theologians and other representatives of Sunni internationalism. Among these Sufis were Sidi Qadi Abul Fadl Iyyad (d. 544/1129), Sidi Abul Fadl ibn an-Nahwi (d. 513/1098), and Sidi Abu Abdellah Daqqaq. As had earlier been the case in the days of Sidi Darras ibn Ismail (d. 357/942), scholars from the city of Fez were instrumental in furthering this latest attempt of reform.

The Harzihimi rabita

A major centre of the dissemination of usuli doctrines in Fez was the rabita, Sufi hermitage, of Sidi Abu Mohammed Salih ibn Harzihim (d. after. 526/1111).

The Ibn Harzihim (Harazem) family, who traced their ancestry to Sidna Uthman ibn ‘Affan (may Allah be satisfied with him), the third caliph in Islam, had been prominent in Fasi scholarly circles for more than a century. As the scion of this family of religious notables, Abu Mohammed Salih had the financial means to travel as far away as Jerusalem for education where he studied I’hya’ ‘ulum ad-din under Shaykh al-Ghazali himself and Baghdad where he was initiated into the Sahrawardiya tradition under the order’s founder Sidi Abu Najib as-Sahrawardi (d. 563/1148). Shaykh Sidi Abu Hamid al-Ghazali, on the one hand, took the patched cloak (khirqa) from Sidi Haramayn Juwayni, who had it from Sidi Mohamed Juwayni, from Sidi Abu Talib al-Makki (d. 386/971), from Sidi Abu Mohamed Jariri, from Imam Sidi Abul Qacem al-Junaid (d. 297/882). As for Sidi Abu Najib, he was also connected to Imam al-Junaid through Sidi Omar Bickri, Sidi al-Qadi Wajduddin, Sidi Mohamed Bickri and Sidi Mohammed Dinnuri.

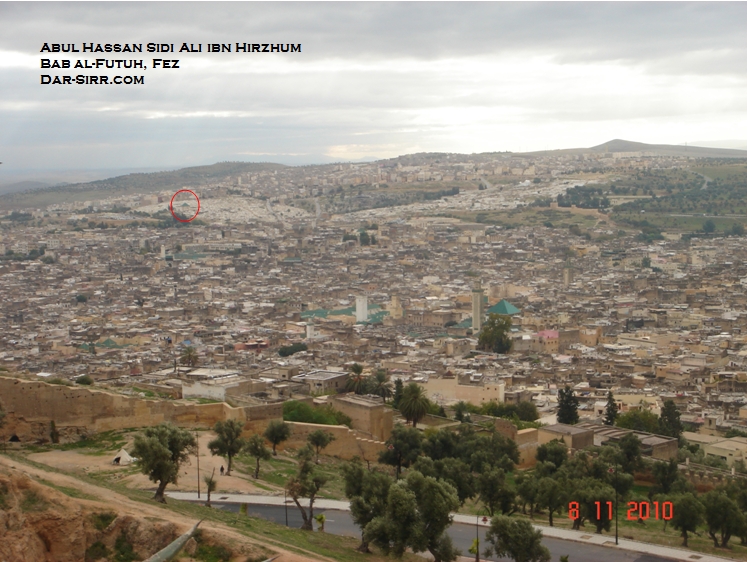

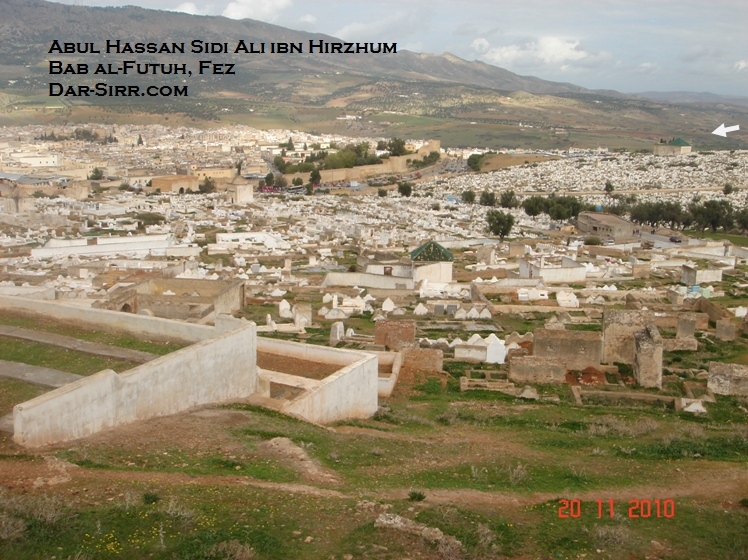

Upon Sidi Abu Mohammed Salih’s death and burial outside Bab al-Futuh in Fez, he was succeeded as head of the Ibn Harzihim rabita by his nephew Sidi Abul Hassan Ali (d. 544/1129), the famous “Sidi ibn Harzihim” of Fez. Shaykh Sidi Ali ibn Harzihim in genealogically connected to Sidna Uthman ibn Affan through his father Sidi Ismail, ibn Mohammed, ibn Abdellah, ibn Harzihim (may Allah be satisfied with him), ibn Zayyan, ibn Yusuf, ibn Sumaran, ibn Hafs, ibn al-Hassan, ibn Mohammed, ibn Abdellah, ibn Omar, ibn Uthman ibn Affan (may Allah be satisfied with him). Despite his uncle’s passionate adherence of al-Ghazali’s teaching, however, the younger ibn Harzihim initially disproved of I’hya’ ‘ulum ad-din and even agreed with its banning, until his opinions were changed by a dream in which the Prophet Sidna Mohammed (peace and blessing be upon him) wiped him for his mistaken beliefs. Henceforward, and especially after he affiliated to the path of al-Ghazali through his disciple Sidi Abu Bakr ibn al-Arabi (d. 543/1128, buried outside Bab al-Mahrouq in Fez), Sidi Ali ibn Harzihim became one of the most outspoken defenders of al-Ghazali in Morocco and devoted the rest of his life to teaching the I’hya’ to his students, who had to copy the full text of the book every year.

Education and personal character

Largely because of his role in disseminating the works of al-Ghazali, Sidi Ali ibn Harzihim was one of the most influential Moroccan Sufis of the formative period. Biographical sources reveal him to have been a highly complex individual whose teaching represented the work of the giant masters of the Maghrib: Sidi Salih ibn Harzihim, Sidi Abu Bakr ibn al-Arabi (d. 543/1128), and Sidi Ali Boughaleb (d. 568/1153, buried inside Bab al-Futuh, Fez). He was an accomplished legal scholar and well-versed in the sciences of hadith and Quranic exegeses and had a fondness for Kitab ar-ri’aya li huquq Allah, al-Muhasibi’s treaties on Sufi psychology and ethics. This work, along with al-Ghazali’s of I’hya’, was a required text for Ibn Harzihim’s disciples. In his personal comportment, he was the quintessential ’abd salih: pious and ascetic, modest in dress, morally virtuous, of an open demeanour, and pleasant in nature. All who met him were moved to affection for him. Upon inheriting a considerable sum of money from his father, he gave all of it to the poor. He also respected learning of all kinds and stove to improve the quality of education in Fez, where he was born, and in Marrakech, where he was eventually exiled.

Moroccan Path of Blame (tariq al-malama)

Despite his reputation as a salih, Ibn Harzihim was also the founder of Moroccan Path of Blame (tariq al-malama). In Ibn Harzihim’s case, however, malamati behaviour did not imply the open contravention of the Shari’a that earned antinomian extremists the censure ulama throughout the Muslim world. What prompted the Almoravid elite to disapprove of him were rather his politically motivated disregard for the prerogatives of rank, his apparent pretentiousness in referring to himself as the Axis of the Maghribis (Qutb al-maghariba), and his outspoken criticism of the Almoravides for their ethnoclassicism and prejudice. Apart from seeing the role of the salih as one of political activism, Ibn Harzihim did little more than heed the advice of Sidi Hamdun al-Qassar Nisaburi (d.271/884), the reputed father of the Malammatiya: “Avoid impressing human beings at all times and avoid seeing their pleasure in any type of characteristic or behaviour. If you do not, you will soon be blamed for what God agency has caused you to possess.”

Exile in Marrakech

Even the forced closing of Ibn Harzihim’s rabita and his exile to Marrakech could not silent this saint’s bitter tongue. The most detailed account of his sojourn in Marrakech appears in at-Tadili’s at-Tashawwuf and forms a postscript to the arrest and execution of the Andalusian Sufi Sidi Abu Hakam ibn Barrajan in 536/1121. No anecdote more clearly illustrates Ibn Harzihim’s opposition to the Almoravid regime and his contempt for its policies. In the following passage, the saint’s success in occupying the moral high ground causes Sultan Ali ibn Yusuf to back down from a confrontation over the burial of Ibn Barrajan (whose recently restored tomb can still be seen in Marrakech). It is easy to imagine how the Sultan equivocal response to Ibn Harzihim’s challenge played into the hands of the opponents of the Almoravids in their ongoing attempt to undermine the legitimacy of Sanhaja rule:

When Abul Hakam ibn Barrajan was ordered to be brought from Cordoba to Marrakech, he was asked about the matters causing his censure and brought them forth, commenting on their implications and differentiating [his beliefs] from those for which he was accused. Abul Hakam said: “By God, I will not live, and the one who brought me here [i.e. the Sultan] will not live after my death!” Then Abul Hakam died [i.e. was executed] and the Sultan commended that he be thrown onto the city garbage heap and that no one make the funeral prayer for him. This command was authorised by the jurists who were their accusers.

A black man who worked for Ali ibn Harzihim and attended his lessons went to [the Shaykh] and told him what the Sultan had ordered concerning Abul Hakam. Then Ibn Harzihim said to him, “If you wish to sell your soul to God, do what I tell you.” “Command what you wish and I will do it,” the man replied. [The Shaykh] said, “Proclaim in the streets and markets of Marrakech: ‘Ibn Harzihim orders you to be present at the funeral of the Shaykh, the legist, the exalted ascetic Abu Hakam ibn Barrajan. May the curse of God be upon him who is able to come and does not!'” The Man did as he was commanded and when [Ibn Harzihim’s challenge] was made know to the Sultan, he said, “He who is aware of Ibn Barrajan’s excellence and is not present will be cursed by God.”

Disciples and followers

At the time of Shaykh Ibn Harzihim’s exile in Marrakech, some of his disciples had already established new rabitas of their own in Fez and beyond. Of these we mention

This latter was praised by later generation as “the saviour of the people of Fez from anthropomorphism” (munqidh ahl Fas mina tajsim) and he rose under the Almohads to become the foremost expert on philosophical theology in all of Morocco. His best known work is a creedal manifesto (‘aqida) entitled Al-‘Aqida al-Burhaniyya. This he dedicated to a female Sufi named Lalla Khayruna al-Andalusiyya. Also allied with the Ibn Harzihim rabita of Fez were a heterogeneous group of Sufis from Sijilmasa on the edge of Sahara desert. However, unlike Shaykhs Abul Fadl ibn Ahmed Sijilmasi (d. 542/1127) and Sidi Mohammed ibn Omar al-Asamm, who were freed after imprisonment and exile in Fez, an important advocate of usul during the same period and a representative of Ibn Harzihim’s rabita in the pre-Saharan oases named Sidi Abu Mohammed Salih u-Imlil al-Munshi (The Polemicist) was assassinated by the Almoravids, like Ibn Barrajan, near the caravan centre of Zagora in the Dar’a valley.

Ref: Article and pictures originally from www.dar-sirr.com